|

Designing

And Growing Community Gardens

|

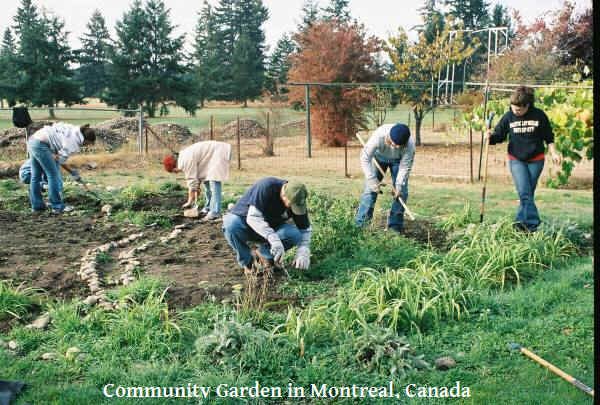

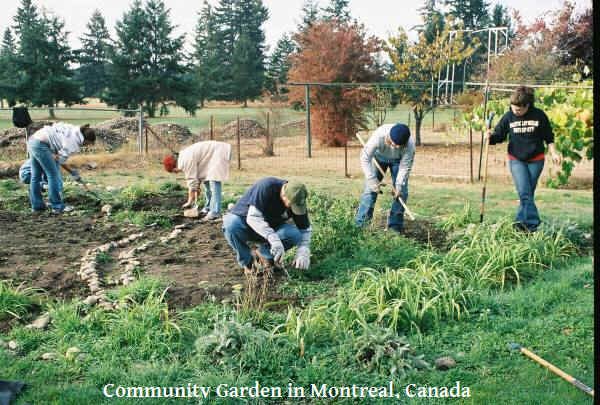

Community gardens vary

widely throughout the world. And there are as many styles as

there are gardeners. It can be a formal foodscape with flowers

and food, rented by anyone who wants to garde, or it can be a

bare bones functional design meant to feed the community, and

without a lot of structure.

In North America, community gardens range from familiar "victory

garden" areas where people grow small plots of

vegetables, to large "greening" projects to preserve

natural areas, to tiny street beautification planters on urban

street corners.

Some grow only flowers,

others are nurtured communally and their bounty shared. There

are non-profits in many major cities, that offer assistance to

low-income families, children groups, and community

organizations by helping them develop and grow their own

gardens. |

In the UK and the rest of Europe,

closely related "allotment gardens" can have dozens of plots,

each measuring hundreds of square meters and rented by the same family

for generations. In the United

Kingdom, community gardening is generally distinct from allotment

gardening, though the distinction is sometimes blurred. Allotments are

generally plots of land let to individuals for their cultivation by

local authorities or other public bodies—the upkeep of the land is

usually the responsibility of the individual plot owners. Allotments

tend to be situated around the outskirts of built-up areas. Use of

allotment areas as open space or play areas is generally discouraged. There

are an increasing number of community-managed allotments, which may

include allotment plots, and a community garden area, many of them

overseen by the Federation of City Farms and Community Gardens.

In Japan, rooftops on train

stations have been transformed into community gardens and gardens for

those who do not have space to grow their own. Plots are rented to local

residents. These community gardens have become active open spaces. And

they're also geared toward giving stressed-out commuters a place to unwind

and meditate. The most well-known is the Machinaka Vegetable Garden-Sorado

Farm. There are currently five Sorado farms in operation, the largest of

which is on top of the JR Ebisu station in Tokyo. For an annual fee of

just under $1,000 per year in the JR Ebisu garden, anyone can rent a plot

that measures about 32 square feet. The fee includes gardening supplies.

Still sounds pretty pricey to me. Then again, it's in the heart of Tokyo.

Repurposing unattractive, unused spaces into food gardens is a great idea

for a lot of reasons. As one would expect, the Japanese rooftop community

gardens are well-thought out, aesthetically pleasing, and neat as a pin.

In the developing world,

commonly held land for small gardens is a familiar part of the landscape,

even in urban areas, where they may function as market gardens. They also

practice crop rotations with versatile plants.

Community gardens are often

used in urban neighborhoods to alleviate the food desert effect. Food

accessibility described in urban areas refers to residents who have

limited access to fresh produce such as fruits and vegetables. Food

deserts often serve lower-income neighborhoods usually in which residents

are forced to rely on unhealthy food options such as expensive processed

foods from convenience stores, gas stations, and fast-food restaurants.

Community gardens provide accessibility for fresh food to be in closer

proximity located in local neighborhoods. Community gardens can help

expand the realm for ensuring residents’ access to healthy and

affordable food in a community.

These gardens are a way for a

variety of cultures to come together and create a stronger community.

Focusing on creating equitable and respectful spaces where farming

knowledge can be shared is crucial to creating a just food system for all

community members. Communities hold specific knowledge and expertise about

their local environment, and therefore, community members have the power

to play a central role in the creation of their local food system.

Partnerships between academic researchers, farmers/practitioners,

advocates, and community members will filter knowledge of healthy foods

and farming techniques throughout the community as a whole. All of these

benefits will lead, in researcher Montenegro de Wit's opinion, to "a

more egalitarian food system" that "will likely emerge from

participation by those traditionally excluded from it.

Community gardens may help

alleviate one effect of climate change, which is expected to cause a

global decline in agricultural output, making fresh produce increasingly

unaffordable.Co mmunity gardens are also an increasingly popular method of

changing the built environment in order to promote health and wellness in

the face of urbanization. The built environment has a wide range of

positive and negative effects on the people who work, live, and play in a

given area, including a person's chance of developing obesity Community

gardens encourage an urban community's food security, allowing citizens to

grow their own food or for others to donate what they have grown.

Advocates say locally grown food decreases a community's reliance on

fossil fuels for transport of food from large agricultural areas and

reduces a society's overall use of fossil fuels to drive in agricultural

machinery.

These gardens improve users’

health through increased fresh vegetable consumption, and providing a

venue for exercise. A fundamental part of good health is a diet rich in

fresh fruits, vegetables, and other plant based foods. Community

gardens provide access to such foods for the communities in which they are

located. Community gardens are especially important in communities with

large concentrations of low socioeconomic populations, as a lack fresh

fruit and vegetable availability plagues these communities at

disproportionate rates.

Community and school gardens have been

shown to have positive health effects on those who participate in the

programs, particularly in lower rates of obesity in school children.

Many studies have been performed largely in low-income, Hispanic/Latino

communities in the United States. In these programs, gardening

lessons were accompanied by nutrition and cooking classes, and optional

parent engagement. Successful programs highlighted the necessity of

culturally-tailored programming.

There is some evidence to suggest that

community gardens have a similar effect in adults. A study found that

community gardeners in Utah had a lower body mass index than their

non-gardening siblings and unrelated neighbors. Administrative

records were used to compare body mass indexes of community gardeners to

that of unrelated neighbors, siblings, and spouses. Gardeners were less

likely to be overweight or obese than their neighbors, and gardeners had

lower body mass indexes than their siblings. However, there was no

difference in body mass index between gardeners and their spouses which

may suggest that community gardening creates healthy habits for the entire

household.

Participation in a community garden has

been shown to increase both availability and consumption of fruits and

vegetables in households. A study showed an average increase in

availability of 2.55 fruits and 4.3 vegetables with participation in a

community garden. It also showed that children in participating

households consumed an average of two additional servings per week of

fruits and 4.9 additional servings per week of vegetables.

The gardens bring urban dwellers closer to

the source of their food, and break down isolation, by creating a social

community. Community gardens provide other social benefits, such as the

sharing of food production, knowledge of the wider community, and safer

living spaces. Active communities experience less crime and

vandalism.

|

Big Bag Bed comes in

sizes up to 12 ft. long. Inserts placed internally in the bed aid

in keeping raised beds upright. No construction required. The Big

Bag also air prunes roots while protecting plants from underground

pests Just unfold, fill and plant. They are usually placed on the

ground, but i like this wooden enclosure thing better. The built

wood frame in this garden keeps the heavy full bag from sagging,

keeps the garden level for disabled gardeners, and gardeners who

just don't want to keep bending down. Easier to water, weed and

fertilize. And easy to harvest your crops. The bag gardens in wood

enclosures are a great idea for your own garden. Elevated cedar

raised bed gardens cost upwards of $100 each, and are only about 4

ft. long. And they are not even half as deep as these bag

gardens. I use the cedar beds when i find them on sale,

because i decorate them with mostly floral plants and fountains. I

would opt for these for an intense and space-saving vegetable

garden.

The bag-in-a-box idea shown here, keeps weeding chores to a

minimum, the community appreciates the neatness, the plants are

snug and keeps critters from bothering them. Awesome. I use the

smaller (7-10 gallon) sizes as portable large planters when i

start shrubs that i don't want to put in the ground yet, until I

have a plan. The smaller bags have handles, and i find it way

easier to move them around than plastic pots. These are a blessing

for all gardeners, but especially those with special gardening

needs. You can grow an entire garden in one of the Big Bags, and

community gardens can designate a bag for each crop, which makes

it more organized. Or an allotment garden can be planned so that

each gardener grows their crops in a "rented" bag. At

the end of the season, you can leave the soil in. The bags are

weatherproof. |

Land for a community garden

can be publicly or privately held. One strong tradition in North American

community gardening in urban areas is cleaning up abandoned vacant lots

and turning them into productive gardens. Alternatively, community gardens

can be seen as a health or recreational amenity and included in public

parks, similar to ball fields or playgrounds. Historically, community

gardens have also served to provide food during wartime or periods of

economic depression. Access to land and security of land tenure remains a

major challenge for community gardeners and their supporters throughout

the world, since in most cases the gardeners themselves do not own or

control the land directly.

Types

of gardens

There are multiple types of

community gardens with distinct varieties in which the community can

participate in.

-

Neighborhood gardens

are the most common type that is normally defined as a garden where a

group of people come together to grow fruits, vegetables and

ornamentals. They are identifiable as a parcel of private or public

land where individual plots are rented by gardeners at a nominal

annual fee.

-

Residential Gardens

are typically shared among residents in apartment communities,

assisted living, and affordable housing units. These gardens are

organized and maintained by residents living on the premise.

-

Institutional Gardens are

attached to either public or private organizations and offer numerous

beneficial services for residents. Benefits include mental or physical

rehabilitation and therapy, as well as teaching a set of skills for

job-related placement.

-

Demonstration Gardens

are used for educational and recreational purposes in mind. They often

offer short seminars or presentations about gardening, and provide the

necessary tools to operate a community garden.

-

Plot

size

In Britain, the 1922 Allotment

act specifies "an allotment not exceeding 40 [square] poles in

extent". In practice, plot sizes vary; Lewisham

offers plots with an "average size" of "125 meters

square". In America there is no standardized plot size.

Community gardens may be found

in neighborhoods, schools, hospitals, and on residential housing grounds.

The location of a community garden is a critical factor in how often the

community garden is used and who visits it.

The site location should also

be considered for its soil conditions as well as sun conditions. Solar

conditions are of paramount importance, as above ground gardening is

always possible. An area with a fair amount of morning sunlight and shade

in the afternoon is most ideal. While specifics vary from plant to plant,

most do well with 6 to 8 full hours of sunlight.

Plant

choice and physical layout

While food

production is central to many community and allotment gardens, not all

have vegetables as a main focus. Restoration of natural areas and native

plant gardens are also popular, as are "art" gardens. Many

gardens have several different planting elements, and combine plots with

such projects as small orchards, herbs and butterfly gardens. Individual

plots can become "virtual" backyards.

Regardless of plant choice,

planning out the garden layout beforehand will help avoid problems down

the line. According to the Arizona Master Gardener Manual, taking

measurements of the garden size, sunlight locations and planted crops vs.

yield quantity, will ensure a detailed record that helps when making

decisions for the coming years. Other consideration to garden layout would

be efficient use of space by using trellises for climbing crops, being

mindful of taller plants blocking sunlight to shorter plants and plants

that have similar life cycles close together

Gardeners may form a

grassroots group to initiate the garden, such as the Green Guerrillas of

New York City,

or a garden may be organized "top down" by a municipal

agency. |