Lazy Gardener's Guide To Composting

I admit it... I'm a lazy part-time composter.

I should do it more often, but i keep adding more garden chores to the list, and

there is necessarily an order of importance in my schedule.

I'm not often in the mood for the added chore of composting thowaway food, and i

don't feel like turning it over and doing all the other things you do for hot

compost. I am a prime example of a lazy gardener finding the easy way out every

chance i get. Living in a city makes the food compost thing a potential

"rodential" problem, so i do this like i do everything else in the

garden. Quick, clean, simple, and not a lot to remember.

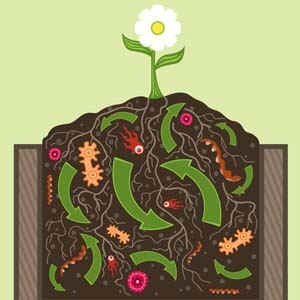

Cold composting is something i prefer...collecting yard waste i've created, and then throwing it into something that serves as a bin. I do not do open compost "piles". I do not throw food garbage into it, except for eggshells and coffee grounds. And the cans do not need to have holes punched into them. So that's how my trash pails spend their winter vacations.

In the 6 months i wait for spring to return, the stuff is slowly cooking. I keep it outside, at the bottom of my kitchen stairs. Because honestly.... i'm not walking far to dump stuff into it in the dead of winter. I'll jiggle or kick it now and then to move it around, but it's pretty much on its own for the winter. I get a lot of packages filled with the horrid shredded newspaper, and i throw that in, too. I avoid throwing in weeds that go to seed. That's the last thing i want to plant in the spring. I eliminated my grass, so there are just a few sprigs that i pull out when weeding and they get tossed in.

My favorite debris are the millions of leaves that fly over my fence somehow and into my flower beds. Some stay put as a winter mulch. A lot of it is put into burlap bags with the equally horrid bubble wrapping i saved, and that is wrapped around my prize plants and trees for winter Protection. Interestingly, i see the same leaves that i use for mulches in the spring sitting in the same place, that don't seem to have broken down at all after winter in the open air. It forms a thick mat when wet. It's a great protection for plants, but you can't get rid of it. I've had most of the same leaves in burlap bags for winter tree wraps for years.The cold compost decomposes slower than the "hot mess", but i'm in no hurry. If I throw yard waste into a separate pail or two all summer, I can make up for the longer time i have to wait for the end results..

I combine wet and dry stuff. The clippings and twigs with leaves that i left in the wheelbarrow that got wet sit there for a few days, and when the water starts to get smelly, into the pail it goes. Along with the dry newspaper, an endless supply of cardboard from mailing boxes (plain brown) with dry leaves and small branches. I throw a bag of potting soil and or manure in, then more yard debris. The smaller the pieces in the compost bin, the faster it decomposes. I was considering adding some awesome worms that reside in the gardens, but i'm not sure they'd like being stuck in that can all winter. And i really don't want to poke expensive galvanized trash cans full of holes, so no oxygen for the worms is an issue. My pails eventually get holes in them naturally. That's when I'll be more serious and experiment with vermiculture. I don't compost food scraps, so odor and vermin isn't ever an issue. By the way.....Do NOT throw pet waste into the compost pail. Ever.

When the concoction is dry and crumbly in spring, I mix another bag of soil or peat moss into it, let it sit for a week, and then it gets mixed together and spread around. I sometimes soak some of the compost in a wheelbarrow for a few days in water or rain to make a compost tea to water directly into some planters. I have found containers with soil and debris filled with water after the winter that have made the tea themselves. We've all done it..... turn over pots, pails or neglected wheelbarrows that have no drainage holes, that you assumed you emptied. After a few days you find that yucky brown smelly water caused by decomposition. That's for your plants to enjoy. Liquid Gold. Sorta the same concept as composting, but impromptu. At the end of winter, and before the cherry trees blossom, those galvanized pails will go back in the alley and join their friends, holding the stuff for the trashpersons to empty again. Circle of Life.

Worms In The Garden

Vermiculture. Why not just call it wormiculture?

Worms are your friends. I used to view them as teenier, slimier versions of snakes with no faces. I detest snakes. On the other hand, i was fully acquainted with the usefulness of worms as a child on fishing trips, and I did what i had to do to catch a fish, so the eeeew factor was quite diminished when i began gardening. And to this day, i will keep leftover worms from fishing trips in my fridge for the next trip, if i have to. Or i'll set them free in the garden. I think my record for worms in whatever they are packed in for fishing surviving in good health in my fridge is a little over a month. They still startle me when i accidentally dig them up while gardening, but i handle and move them calmly with my gloves on, and we both go on our merry ways, peacefully tending to the garden chores. Out of sight, out of mind. I can even feel bad when a robin somehow pulls out an unsuspecting worm from underground, like a magician pulling a rabbit out of his hat, to feed to his family.

Someday, i'll start a food pile compost pile, but for now, i'll stick to yard debris and such.

I clearly remember the year i "planted" a few hundred worms, along

with perennials, in a newly-landscaped garden.

I was shocked that there was not a worm to be found on the land when i started.

Almost every eighbor poisoned their lawns on a monthy schedule with chemical

pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers and who knows what else. The

allegedly lived in fear of the dreaded Mole Cricket. My land was being poisoned

by their runoff and errant spray. I had no worms, (no mole crickets, either,

despite not using chemicals) and i knew that being wormless didn't bode well for

my garden or robins. And by the way.... the disgusting giant flying cockroaches

(deceptively and politely called Palmetto Bugs, when they should be designated

the state bird), and their cousins, the familiar common cockroach, were

impervious to the lawn chemical bombardment.

So, risking being labeled a "Yankee Frootloop", i adopted a large colony of worms that i immediately set free to burrow into the soil and work their magic in the gardens. A few months after "planting", (by planting, i mean tossing a bag's worth of them gently into the air for a scattered soft landing on my soil) they had created quite an underground community. I never quite figured out why worms wouldn't just wiggle away when you placed them in your garden. Mine were perfectly happy and colonized quickly. By the way, less than 5 minutes after being lightly tossed onto the soil, those worms had already nosedived and wiggled their ways underground. I presently have a large community of healthy night crawlers that i intend to employ in a composting endeavor. Very few people poison their lands in my new environment. If you are a gardener, and don't find worms often in your garden, you might want to order live worms and give them a home. You don't need a lot. I hear that happy worms can double their population in 60 days.

Lots of places online sell them by the bag or by the case of hundreds. They're Mother Nature's soil aerators and fertilizers. Some gardeners invest in expensive garden soils that contain worm "castings". I personally find that a bit expensive, when it's easier to just plant live worms who will work all day leaving castings for years digging in the garden.

Vermiculture as a garden composting concept is a little different. It's what I described above, but created in an enclosed and controlled environment. Those are working worms. I am not going to start a worm farm, but i am eventually going to give them a happy home in my compost cans over winter, set them loose in the garden in spring, and repeat.

Article from Cornell University

About those worms.....

Earthworms are voracious consumers of organic materials and leave a nutrient rich manure called castings in there wake as they work their way through the soil, cycling nutrients between the soil surface and as deep as six feet below. As the castings are neutral in pH, healthy earthworm populations can help to mitigate problems with either high or low pH. In addition to producing up to half of their body weight in nutrient rich castings every day, earthworms also improve garden soils by creating channels which help to aerate the soil and improve drainage, while their slimy, nitrogen-rich secretions help to bind soil particles and increase moisture retention. A soil that is host to a burgeoning earthworm population is likely to be nutrient rich, highly friable, and a joy in which to garden.

Even though the earthworm is actually an 18th century European immigrant to

North America, it has since become fairly ubiquitous across the continent. Rich

organic soils are reported to harbor up to a million earthworms per acre. So if

you want a healthy earthworm population in the garden, it's generally not so

much an issue of "importing" worms as it is providing optimal

conditions for them to prosper. Avoiding practices that damage or discourage

worms, such as applying chemicals, excessive rototilling or spading, as opposed

to using a digging fork which leaves the worms unharmed, can also help increase

populations.

For earthworms to thrive, they need an ample supply of organic matter, adequate

moisture, and oxygen. Additions of compost or well-rotted manure to the soil and

thick mulches of shredded leaves, grass clippings, and other organic materials

will encourage worm activity by providing food and habitat. In soils that have

been severely depleted or heavily treated with chemical fertilizers and

pesticides it may take many years to build healthy populations. If good

conditions are present for worms and none at all are spotted for a year or two,

it might help to bring in a can full of worms from a neighbor's garden for

"breeding stock." One of the best gifts my wife and I received when we

got married was a can of fat earthworms that we tucked under a pile of mulch in

our new garden. The population has continued to grow ever since, and after five

years, we rarely turn over a fork full of soil without seeing a worm or three.

![]() A

large part of the organic waste generated worldwide ends up choking landfills,

producing harmful greenhouse gases as it rots, and creates serious disposal

problems for local communities. From kitchen waste to livestock manure, there's

just no "over there" to put the stuff any more. Enter the red wiggler

worm. From small bins in pantries and cellars, to large-scale commercial

vermin-composting operations, billions of red wigglers are literally eating our

garbage. On the output end of the system, the use of nutrient-rich, worm casting

based products, instead of mined chemical fertilizers, further helps to protect

the earth, air, and water from toxic pollution.

A

large part of the organic waste generated worldwide ends up choking landfills,

producing harmful greenhouse gases as it rots, and creates serious disposal

problems for local communities. From kitchen waste to livestock manure, there's

just no "over there" to put the stuff any more. Enter the red wiggler

worm. From small bins in pantries and cellars, to large-scale commercial

vermin-composting operations, billions of red wigglers are literally eating our

garbage. On the output end of the system, the use of nutrient-rich, worm casting

based products, instead of mined chemical fertilizers, further helps to protect

the earth, air, and water from toxic pollution.

Unlike Earthworms that burrow deep into the soil, red wigglers work just below

the surface of the soil "litter" converting organic materials into a

rich fertilizer. These amazing creatures can eat up to half of their body weight

every day and can double their populations in as little as three months. They

can eat everything from vegetable scraps and shredded newspaper, to coffee

grounds and filters, teabags, and aged manure, but generally not meat and dairy

products, although some vermicomposters report success with them in small

amounts. The worms can survive at temperatures from around 50–90°F (10–30°C)

but near 70°F (20°C) is optimal, so in northern climates year-round

vermiculture is an indoor activity. A well maintained worm bin has little or no

odor though, so that shouldn't be a problem. The important thing for a pest and

odor free bin is to feed the worms only what they can eat and to keep the

surface covered with wet burlap or other material.

Cornell University - Worms and Composting

Natural Pesticides and Fungicide

|

Quick Links |

Content, graphics and design

© 2020 Mary's Bloomers

All rights reserved

This site uses Watermarkly Software